www.somalilandintellectualsinstitute.org

Introduction

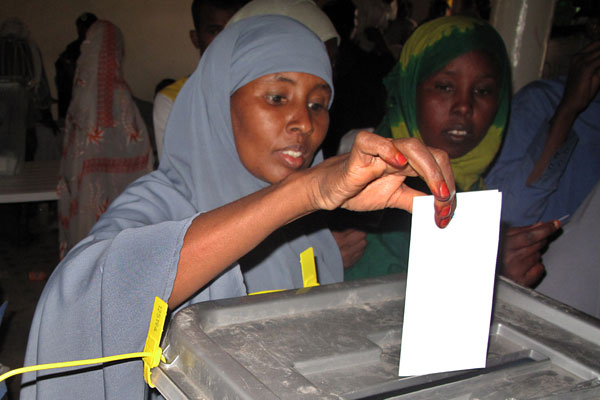

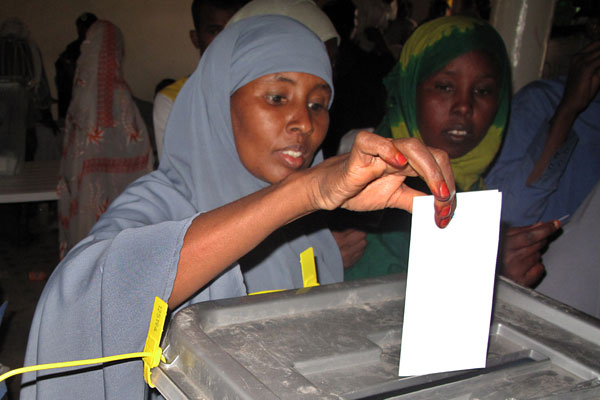

Since Somaliland withdrew from its union with Somalia in 1991 a nascent democratic system has been implemented. The national charter approved soon after the union withdrawal established a government where the power-sharing system was based on clan lines. Subsequently, the constitution of the republic, which was approved by a unanimous national referendum in 2001, stipulates that from the date of approval of the constitution the country directly transfers to a multiparty democratic system instead of a clan system.

Since then, a number of successful elections have been held including a local municipality, presidential and parliamentary. However, there have been some post-election security problems in 2012. The main cause of such conflict was attributed to the fact that before the elections a registration of political parties was reopened.

The three political parties that secured the most votes in all of the Somaliland regions would officially be considered National Political Parties. Such competition resulted in each Somaliland Clan establishing a party of its own.

If Somaliland goes through the same procedure again it could result in huge damage to its democratic system and its peace as well. Because it will cause each clan to establish its own party, this could subsequently result in any party defeated in the elections being interpreted as clan failure, not party failure.

Therefore this study will examine how clan politics shapes Somaliland’s democracy and the effects it has. The latest municipality elections in 2012 will be used as a case study by the researcher. This paper will consist of five main sections including the introduction, literature review, research methodology, analysis, and conclusion.

Overall aim and Objectives of the Study

The overall aim of this study is to discuss clan politics in Somaliland and how such a kind of democracy could either make or break Somaliland. The objectives of this research are: To investigate the pros and cons of the democratic system that Somaliland exercises. To explain how clan politics in Somaliland can either contribute to the stability of the country or endanger it. To describe the relationship between electoral process, political parties, and clan democracy through the example of the Somaliland Local Government Election of 2012. To put forward possible solutions.

Research Question: How does clan politics affect democracy in Somaliland?

When Somaliland gained its independence from the British on 26th June 1960 it joined South Somalia in 1st July 1960, with limited or no governmental experience, to form the Somali Republic. After a few corrupt years with civilian governments, a military coup occurred in October 21st, 1969 and the state was under a totalitarian administration for more than two decades until 1991.

Once Somaliland withdrew from the union in 18 May 1991, with little or no experience concerning democracy and other governmental systems, the people agreed to stick with the traditional system meaning that all governmental positions were to be based in clan power sharing. The traditional system of life has been so strong inside societies. Even today there is clan responsibility for each event instead of individual responsibility and the traditional customary law is still strong enough to dominate.

The traditional system succeeded in disarming and stabilizing the majority of the country but it was short on developing the country further. A democratization system was introduced through the Somaliland constitution, approved in a national referendum in 2001. This system has never been easy to follow or further develop. The people of Somaliland have been struggling to build a state and democratize it. Although the institutions and the structures are in place the mentality of the people and the poor legal framework on elections meant that Somaliland has been far away from the ideal of democracy.

Somaliland conducted a number of elections since the constitution of the republic was approved which stipulating a multiparty system of democratization as illustrated in Article 9(1) “The political system of the Republic of Somaliland shall be based on peace, co-operation, democracy and plurality of political parties” (Somaliland Constitution). The elections conducted after that were at all levels and were successful for an unrecognized and underdeveloped country in Africa with limited resources.

The system worked very well in the first decade. A number of elections were conducted including municipality elections in 2002, presidential elections in 2003, parliamentary elections in 2005 and presidential elections in 2010. However, the system was hindered by a poor legal framework for the election, strong traditional or clan politics and representation, and the legacy of the totalitarian government.

What Went Wrong in the Municipal Elections in Somaliland in 2012?

Somaliland’s adoption of a hybrid system, by sticking with traditional institutions like the Upper House of the Parliament (which is called Guurti) and which is selected in clan lines, and introducing the multiparty democratic system, have been successful and brought political progress to Somaliland (SONSAF, 2012; Jhazbhay, 2008). Before the municipality elections in 2012 there was a political parties’ registration.

This occurred after the president, Silanyo, appointed a committee in March 2011 to assess whether the country needed more parties than those qualified to be National Political Parties (Udub, Kulmiye and Ucid).

The constitution grants the right to formulate a political party to every citizen in Article 9(1) while in Article 9(2) limits the number of National Political Parties into three. After three months of research and consultation with the citizens the committee concluded that the majority of the people were in favor of reopening the political parties’ registration. Some measures have been taken to enable such a decision.

The electoral laws, Law No 14 and Law No 20, have been amended and a National Registration & Approval Commission of Political Associations RAC has been appointed by the president. There were fifteen new political associations and the three previous National Political Parties, but nine of them have been disqualified because they failed to satisfy the legal criteria for selection in the constitution and other electoral laws.

The RAC stated that disqualified associations failed to prove that they had an office as well as 1,000 registered members in each region in Somaliland. This caused some friction between the disqualified associations and RAC (Saferworld, 2013, 20). Two associations among the nine qualified association, Nasiye new association and Somaliland’s former ruling party Udub, withdrew from elections before the list of the candidates in municipality elections was submitted to the NEC due to some internal problems. The other seven parties (KULMIYE, UCID, UMADDA, DALSAN, RAYS, WADANI and XAQSOOR) were approved to run for municipality elections. Beside the gaps in the electoral laws of the country there were two main concerns.

The first was that most of the parties were allied with two or more Somaliland clans and any result was difficult to satisfy. The second was that no voter registration was available in the elections so that double voting was very easy.

Gaps in the Somaliland Elections Legal Framework

One of the main legal frameworks is that the constitution of Somaliland in its Article 9 allows a multiparty political system in sub section 1: “The political system of the Republic of Somaliland shall be based on peace, co-operation, democracy and plurality of political parties”. While in sub section 2 it limits the number of the political parties to three “The number of political parties in the Republic of Somaliland shall not exceed three (3).” In Article 9(3) it illustrates that “A special law shall determine the procedures for the formation of a political party, but it is unlawful for any political party to be based on regionalism or clanism” (Somaliland Constitution Art 9).

Then, the parliament adopted a Political Parties Law no 14/2001 and Presidential and Local Elections Law 20/2001, in line with its 9(A). The former Act discussed the formations and political parties and the way they could qualify as National Political parties, and the latter discussed the procedure of the elections, eligibility of the candidates, the term and so on.

Both acts underwent extensive amendments.

The Political Parties Law mentioned that the three parties that win the majority of the seats in the 2002 municipality elections will directly qualify to be the National Political Parties which will have the sole right to nominate candidates in the parliamentary and presidential elections but the act came short as to whether the three national political parties will stay for infinity or the same procedure will be applied in each municipality election.

The Act also, in its Article 6(2), states that any person who is going to be a candidate in elections – whether presidential, parliamentary or municipality – shall be nominated through a political party. This contradicts with Article 22 of the constitution, which gives any citizen the right to run for elections when he/she satisfies the personal criteria.

One big concern is in Article 11(2) of the Presidential and Local Elections Law 20/2001 which discusses the appointment of the National Electoral Commission. It illustrates that the commission will contain seven members; three appointed by the president, two members will be appointed by the two political parties, and the last two will be appointed by the two opposition parties.

So, if the president appoints three out of the seven members, which constitutes almost 43% of the commission votes, we can understand how challenging it is to accept that they are impartial. Although there were extensive amendments of these laws there is still work to be done.

Clan Representation in Somaliland’s Elections

According to Prof. Hussein A. Bulhan, “A [Somali] person’s genealogy is his identity and social security.

It defines his rights and position in society” (Bulhan, 2013, 71). This illustrates that for Somalis the clan is the one who defines not only their social status but also their political orientation. Somaliland is populated by four main clans: Isaaq, Samaroon, Harti and Issa. Issa populated some towns which are located near the border of Djibouti. Samaroon also dominates mainly in the towns located to the west of Hargeisa. Isaq, the majority clan, resides from Gabiley to Erigavo as well as in most of the main cities that brought majority votes like Hargeisa, Burao and Berbera.

The Harti populates from Erigavo to the east, even in Puntland. One major clan that is scattered through Somaliland is Gaboye, which are not concentrated in one area and is a marginalized clan in Somaliland. The political implication is that each party attracts a shadow president and vice president from Isaaq and Samaroon as they make up a high majority of the country.

In addition, there is a big rivalry among Isaaq sub clans and some of them try to make an alliance with Harti sub-clans. The clan rivalry is usually highest when ever elections come closer. From Somaliland’s formation in the early 1990s, its foundation was based on clan lines. The Somaliland National Charter 1993 was approved at the Borama Grand Conference, at which 150 nominated representatives from all Somaliland’s clans were present.

The charter in its article 10(3), 11(2) stipulates that the House of Elders and House of Representatives will be elected along clan lines. In addition, the Charter’s Article 16(6) states that the president and vice president will be elected at the Borama Conference by clan representatives.

The charter states in its Article 5 that the charter will be replaced with the constitution after two years, but that only happened in 2001. The charter worked effectively for Somaliland as to do so along clan lines was the only way to stabilize and disarm Somaliland’s people.

In the municipal election in 2012, Somaliland went back ten years. Instead of democratizing the existing national political parties which were formulated by all Somaliland’s clans, the people decided to establish new political parties and the misfortune was that each clan of Somaliland formulated its own party while sometimes allied with a few other clans.

This caused many results in the elections not be satisfactory. The SONSAF Post-Election Lessons Learned Evaluation Workshop emphasized that when the NEC announced some winners in districts in Marodijex, and then repealed this later and announced other winners, there was tension. In addition, SONSAF’s report highlighted the protest in Ahmed Dhagah District which caused death and injury and was prompted by the announcement of computer data loss by NEC.

Voter Registration in Somaliland

The voter registration law was enacted in 2007 and amended in 2008. (Jama, 2009).

A successful voter registration was implemented and voting in the 2010 presidential elections occurred with little double voting. Due to some minors reaching the age of voting and some errors in the voter registration in 2009, the parliament decided to nullify the voter registration on 13 December 2011. (Saferworld, 2013). This was the only option available as it was impossible to conduct voter registration within few months from the municipality election.

Because of that there was a lot of double and treble voting and most of international observers and papers written after the 2012 elections recommended that there should be a voter registration for each election in Somaliland (Progression 2013; Saferworld 2013).

Research Methodology

Research Design: According to the purpose and objective of the study, the design adopted for conducting this research was an explanatory kind of design to explain Somaliland’s democracy with special attention given to the last Somaliland municipality election 2012. The reason the researcher employed this kind of design is to analyze Somaliland’s democracy in relation to clans and identify whether the system will work with it. In addition the design integrates the views of those most closely involved in the process on how it works.

Data Sources and Type: The data used for conducting this research were obtained from different sources, which can be grouped into two main kinds: primary sources of data collection and secondary sources of data collection. Key informant interviews have been conducted. The researcher has interviewed the various stakeholders including: members of the three national political parties, members from NEC, members from civil society organizations and members of the public.

In addition to that, a wide range of literature has been reviewed including journals, papers and electoral laws. The researcher conducted the analysis through key informant interviews to get first hand information about Somaliland’s clan democracy. Almost all stakeholders have been interviewed including national political parties, electoral commission, civil society and the citizens.

In this section the writer will try to analyze the answers provided by the respondents.

1. What do you think about Somaliland’s democracy? The majority of respondents agreed that Somaliland exercises clan democracy, which looks like the ideal democracy when you are looking at it as an outsider, but when you look at it deeply, you will find that such democracy is based on clan lines.

One example that the respondent from the public gave is that “No one can be a candidate other than for the constituency that his/her clan populates, so when we look deep inside it, its clan democracy. The good thing is that every person can vote for anyone he/she wants without any interference”. The respondent from the civil society organizations underlined that “The people of Somaliland are very smart because they did not copy the whole democracy system as practiced in the Western Countries but they filtered and adopted the elements which are compatible with our culture and religion”.

In turn, the respondent from the UCID opposition party emphasized that: “In fact, the first decade Somaliland benefited from the democracy and we did a considerable progress, but since reopening the political association registration in 2011 each clan formed a party and since then we do not know how much development we made towards democratization”

2. How would you characterize democracy in Somaliland? All the respondents agreed that Somaliland’s democratization in nascent and is growing with time. They underlined that Somaliland’s democracy is better than a lot of recognized African states. The respondent from the WADANI opposition party argued “The politicians are hindering the Somaliland democracy by pursuing their personal gain and interest, there is no ideological support to any political party and they are shifting through the parties for their personal interest”. Map Depicting Somaliland

In addition, the respondent from the National Electoral Commission argued that “the democratization process was on the right track up until the Silaanyo administration which has shifted the entire multiparty system back to the clan sharing ages, and this is not good for democratization because political parties were created to eradicate clan alliances which is not one of the pillars of the democratization”.

3. Bearing the mind the last municipality elections, how does Somaliland’s democracy affect the peace and stability of the country? Most of respondents agreed that the elections happened in a peaceful manner though the lack of voter registration allowed multiple voting by some citizens. Respondents from the public and civil society upheld that the 2012 elections boosted the democratization of Somaliland and happened in a free and fair manner: “2012 elections brought confidence among the citizens. Regions that were not expected to conduct elections by its people have been held and got that constitutional right.

So, the 2012 municipality elections promoted peace and stability of the country” Nevertheless, the respondents of the three political parties highlighted that the last municipality election posed a serious danger to Somaliland’s stability and they attributed this to two factors which are lack of voter registration and reopening the political associations’ registration: “There were a lot of problems in organizing the elections. Conflicts and hostility arose between the people and the government.

It brought a disappointment to the public and it caused the public to refuse the voter registration in 2016 and say we are not going to vote in any elections to come” said a respondent from the Kulmye ruling party.

The respondent from NEC blamed the politicians and traditional elders for the post elections tension: “politicians are using clan relations and any other means that could help them succeed in an office position, in the 2012 municipality election many things went wrong because they were doing whatever it takes for them to be elected and the whole campaign become clan based and for this I blame the traditional elders because for them education is irrelevant and you can see those elected how little they have contributed to the development of the country.”

4. What do you think about Somaliland’s electoral laws? Although some of the respondents did not have much knowledge in electoral laws, the majority believed that there is a gap in electoral laws. A respondent from civil society said: “The Somaliland electoral laws have loopholes which the stakeholders were not able to finalize. For example the parliamentary seats, the demarcation of the boundaries of the districts and regions.” “The unification of electoral laws are missing, the procedure and laws for election of Guurti and Parliament are still missing” the respondent from the public added.

All political parties’ members also highlighted that there is huge gap in the electoral legal framework and suggested the need for scientific and extensive amendments. Respondent from UCID opposition party argued “All the electoral laws whether it be law no. 14, law no. 20 as well the law no. 37, voter registration law, are full of gaps and need immediate and extensive amendments.”

5. What do you think about reopening of political parties’ registration in Somaliland in each decade? Do you think this will contribute to democratization, peace and stability or vice versa? The majority of respondents agreed that the reopening of political association registration can cost the peace and stability of Somaliland but they mentioned that the National Political Parties are locked to all but a few persons and is not a national asset.

So, without democratizing the political parties it will be difficult to refuse such registration. The respondent from WADANI opposition party says “This, [reopening political party registration] will cause the end of classic political party and the birth of a new family party. Instead, the existing national parties shall be capacitated and democratized”.

6. Can you share with me your opinion about the National Political Parties? Do you think there is democracy inside them? All the respondents agreed that there is no democracy inside National Political Parties: “There is no internal democracy in the political parties of Somaliland. The chairman dominates the political parties of Somaliland and it is a one man political party” said the respondent from the civil society organizations.

Another respondent from the ruling KULMIYE party mentioned: “there is no democracy inside them. They should rather democratize the national political parties to formulate a democratic country. The ownership of each national party belongs to the chairperson’s clan and even pays the financial contribution to the party solely” All the respondents show concern about the National Political Parties and highlighted that unless the parties capacitated and democratized Somaliland is in a serious danger of political uprising.

7. Do you think that National Electoral Commission members are impartial and free from clan nomination? All the respondents agreed that the commission is nominated along clan lines: “everyone came from a specific clan, that is why there are not two commissioners from the same clan because it will create rumor that some clans are being promoting while others are not even given a seat” argued the respondent from the NEC. Respondent from UCID show concern at both the number and the nomination of the commission: “The Electoral Commissioners are nominated in line with the Presidential and Local Elections Law No 20/2001.

There are seven commissioners and they are nominated through a clan. A number of clans do not have any representation in the commission and reform is needed with the number of the commissioners so that each clan will have a representative. In addition, the majority of the respondents placed a question mark over the impartiality of the commission.

A respondent from Kulmiye, the ruling party, said: “Their impartiality depends on their criteria of selection.” “I do not think they are impartial and in elections every member usually supports the party that nominated him/her”, added the respondent from the public. However, the respondent from WADANI, an opposition party, believes that they are impartial and argued “The current commission are new and the only task they did is the pending voter registration.

I personally believe they are impartial and have the capacity to successfully conduct the parliamentary and presidential election in early 2017”

8. Can you explain what kind of democracy could suit Somaliland? Clan Democracy or Modern Democracy? Respondents gave a variety of answers to this question. The respondent from NEC argued for modern democracy: “Modern democracy can be much more suitable for Somaliland if we need to become a developed because in democracy education, expertise knowledge all relevant and these things are important for our people to achieve change” she argued.

On the other side, a respondent from KULMIYE, the ruling party, argued vice versa: “In Somaliland we do not need a western democracy, it won’t work for us. We do not need either clan democracy. We need a simple democracy in line with our culture and religion”.

In addition, the respondent from the public agreed with this argument “I just want simple democracy free from clan and everyone can be voted for because of his/her quality not the clan he/she belongs to”. Both respondents from UCID and WADANI parties showed a concern about clan democracy and emphasized that clans caused the loss of ownership in national parties.

They added that nominating civil service staff on a clan basis was deteriorating the development of the country. The most ideal suggestion the researcher admired came from the civil society respondent who argued that the hybrid system is ideal for Somaliland and it just needs to institutionalize and correct some issues: “The country of Somaliland adopted hybrid system which uses both the traditional and modern system.

The hybrid is effective and worked for Somaliland. However we need to capacitate the political parties by building the structure and established permanent members who pay subscription fees.”

Conclusion

Clan-democracy in Somaliland experienced ups and downs as it underwent each new system of government. According to this study the clan democracy model in Somaliland has its positive and negative effects on peace, stability and democracy and this can be illustrated by two periods of time. In the first decade of Somaliland’s democratization, between 2002 and 2012, there was huge political development that demonstrates how clan-democracy developed within this nation.

Most of the respondents in this paper agreed that Somaliland’s democracy was on the right track during that period. The National Political Parties developed to be more democratic and all Somaliland’s people were represented within in each party. As the political association registration reopened in late 2011, a new period of uncertainty began for Somaliland.

Each clan formed its own party and after the 2012 municipality elections political tension was high in Somaliland. Somaliland’s people were disappointed about democratization and some of them have even refused to take part the voter registration in 2016, according to an interview with someone from the KULMIYE party. For clan democracy in Somaliland to be successfully and contribute to the stability and peace of the nation, the study recommends: Scientific amendments to all electoral laws and unification of the laws dealing with all levels of election.

To democratize the national political parties and issue laws monitoring and dealing with their transparency. So, no clan or individual will need to establish his/her own political association. To stop reopening the registration of political association. To enact laws and policies dealing with the towns and regions border demarcation.

References:

- Bulhan, H. (2013). Losing The Art of Survival and Dignity: Transition from self-reliance to dependence and indignity to Somali society. Maryland: Tayosa International Publishing. 71.

- Jama I H, Somaliland Electoral Laws 2009, Somaliland law series, pp 119–120.

- Jhazbhay, I. (2008) ‘Somaliland’s Post-War Reconstruction: Rubble to Rebuilding. International Journal of African Renaissance Studies – Multi-, Inter- and Transdisciplinarity 3(1):59-93.

- Political Parties Law no 14/2001

- Presidential and Local Elections Law 20/2001

- Progressio, 2013. Swerve on the road: Report by Election International Observers on the 2012 local elections in Somaliland.

- SAFERWORLD, 2013. Somalilanders Speak: Lessons from the November 2012 Local Elections.

- Somaliland Constitution

- SONSAF, 2012. Somaliland Pre-Election Consultation.

- SONSAF, 2013. Democratisation Policy Brief on Somaliland’s 2012 Post-Election Challenges and Priorities.

- #Somaliland #Hargeisa #Africa #Democracy #HornofAfrica #Somalia #UnrecognizedCountry

more recommended stories

Somaliland’s Berbera Industrial Park: A New Era of Investment and Job Creation

Somaliland’s Berbera Industrial Park: A New Era of Investment and Job CreationThe Government of Somaliland, under the.

President Irro’s Landmark Visit to UAE: A Diplomatic and Economic Win for Somaliland. Dubai, UAE – Somaliland’s Diplomatic Breakthrough

President Irro’s Landmark Visit to UAE: A Diplomatic and Economic Win for Somaliland. Dubai, UAE – Somaliland’s Diplomatic BreakthroughBy: Abdi Jama President Dr. Abdirahman.

Kenya’s Unjustifiable Interference in Sudan: A Grave Violation of International Law and Regional Stability

Kenya’s Unjustifiable Interference in Sudan: A Grave Violation of International Law and Regional StabilityBy: Abdi Jama Kenya’s continued meddling.

𝗙𝗼𝗿𝗺𝗲𝗿 𝗣𝗿𝗲𝘀𝗶𝗱𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗠𝘂𝘀𝗲 𝗕𝗶𝗵𝗶’𝘀 𝗥𝗲𝗰𝗸𝗹𝗲𝘀𝘀 𝗔𝗰𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻𝘀 𝗠𝘂𝘀𝘁 𝗡𝗼𝘁 𝗕𝗲 𝗜𝗴𝗻𝗼𝗿𝗲𝗱 – Abdihalim Musa

𝗙𝗼𝗿𝗺𝗲𝗿 𝗣𝗿𝗲𝘀𝗶𝗱𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗠𝘂𝘀𝗲 𝗕𝗶𝗵𝗶’𝘀 𝗥𝗲𝗰𝗸𝗹𝗲𝘀𝘀 𝗔𝗰𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻𝘀 𝗠𝘂𝘀𝘁 𝗡𝗼𝘁 𝗕𝗲 𝗜𝗴𝗻𝗼𝗿𝗲𝗱 – Abdihalim MusaYesterday, Somaliland witnessed a deeply troubling.