By Maal Sareeye

The world order as we know it was established on the heels of Germany’s defeat in 1945 in

World War 2 and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 was the coronation of Uncle Sam’s

undisputed domination, standing on top of the “food chain”. Pax Americana that came right after

that change of guard is slowly fading away and the global South, more inclined to sponsor a

multipolar world stage, is not in full control of the world’s affairs yet. If, of course, China and the

United States avoid the ”Thucydides trap” referring to an apocalyptic scenario in which a rising

power aspires to topple the ruling hegemon.

Simply put, we have definitely entered into uncharted territories where the “Westphalian system”,

enacted in 1648, at the origin of statehood and its privilege of exclusive sovereignty over a piece

of land is firmly pushed aside and deliberately challenged. The Russia-Ukraine war and

Venezuela attempted takeover, last year, to snatch a big chunk of his next-door neighbor

Guyana in South America, rich in oil deposits, are both testimonies of this new narrative based

on “might makes right”.

This rhetoric characterizes the approach of an assertive and cunning foe bent on unshackling

himself from the United Nations legal constraints as well as rebuffing the international order

architecture that had so far governed relationships between nations.

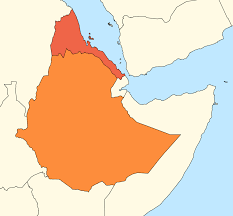

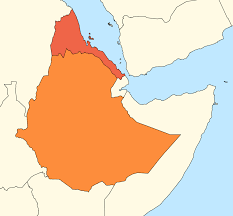

When it comes to the Horn of Africa (HOA) powerful dynamics and how they’re shaping the

regional environment, is it fair to presume Ethiopia-Somalia/Somaliland feud responds to that

definition highlighted above, in relation to Ethiopia’s quest for sea access?

In other words, what dictates a state policy when your long term economic sustainability and

political clout are curtailed by the geography which determines, in return, the pillars of every

country foreign affairs agenda? Furthermore, what are the ramifications on policy-making

strategy when Ethiopia is powerless coping with its “Malthusian crisis” which translates into

population growth outpacing agriculture output and resulting in famine, poverty, diseases,

displacements, etc? How on earth can Ethiopia protect its supply chain routes and commercial

fleet (11 vessels) when its navy doesn’t have a port call on its own?

Finally, one last hurtful statistic : Ethiopia’s GDP could have been 20% higher according to data released during the Bolivia vs Chile’s court hearing under the auspices of the International Court of Justice in 2018.

The culprits are the undesirable repercussions of landlocked country, transit times and transport

costs, forcing, for example, businesses to hold large inventories as a means to hedge against

disruptions, thus weakening their competitive edge. These compelling issues cannot be

overlooked no matter what.

In a nutshell, are these trends impeding economic integration and political stability in the region

plagued, for decades, by extreme violence and fraught with political tensions? Could it be a

recipe for disaster?

The answer is without hesitation yes, so long as Ethiopia’s repeated claims to gain access to the

sea are not met accordingly. Without securing that coveted window, Ethiopia will not achieve

middle-income status by 2025 via export-oriented industrialization nor will it succeed in driving

forward port diversification and competition to lower shipping costs for ethiopian cargo. But

striking deals with Somalia and Somaliland for direct control over its access to the sea is the

missing link, the force multiplier turning Ethiopia into a maritime power and ascending to

greatness. The rest will fall into line afterwards.

Moreover, we must be cognizant of the fact that the HOA commands the Bab el-Mandeb Strait,

18 miles wide at its narrowest point, connecting the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden and by

extension to the Indian Ocean. This chokepoint, critical for the shipping business industry worth

over 2 trillion US dollars, is on the news as the Houthi are wreaking havoc in solidarity with

Palestine.

Therefore, to bypass the roadblock, so to speak, the conventional wisdom would have endorsed

an arrangement framework initiated by HOA main body, IGAD (Intergovernmental Authority on

Development), accommodating Ethiopia’s quest after Eritrea reclaimed in 1993 Assab and

Massawa ports which used to be the backbone of Ethiopia’s economy.

In fact, the UnitedNations has acknowledged non-coastal special needs and challenges by tacklinglandlockedness’s most damaging consequences through the Vienna Action Programme

(2014-2024).

Imagination not being an IGAD common denominator, perhaps the East African Community

(EAC) may ignite the spark recognizing the scope and magnitude of such a predicament and

campaigning that a stable and prosperous Ethiopia, depicted as a consequential shift hard to

dismiss, will prove to be beneficial down the road. Having said that, what does this deadlock

mean in connection with Somalia or Somaliland perspective and both situated strategically?

Entitled to enjoy in perpetuity the continent’s longest coastline (3300 km) stretching from the

Gulf of Aden to the Indian Ocean, the 17 million Somali are, more than ever, at a crossroads.

Their elites, at the forefront and the first concerned, wherever they are on the “tribal spectrum”,

are condemned to cope with Ethiopia (120 million inhabitants combined with a 115 billion US

dollars GDP). Truly speaking, it’s a juggernaut to be reckoned with.

As prime minister Abiy Ahmed has put it ”candidly” during a speech addressing the ethiopian

parliament last year, his fellow nationals won’t live in “a geographical prison” when you take into

account this shipping-related formula for non-coastal countries in order to describe the sheer

volume of goods they need to import (1000 kg per person per year)…and the significant

expenditures that come with. And to make matters worse, Ethiopia, under a severe debt

distress, has defaulted last month on its bond payment for the first time (33 million US dollars).

All things considered, it’s not difficult to fathom a context in which Ethiopia growth engine

benefits spreading all across Somalia and Somaliland, fueled by half dozen modern somali

seaports backed by dynamic and competitive free trade zones, linked by roads and railways to

dry ports popping up along their 1600 km long border, all the way to landlocked countries, the

likes of South Sudan, Uganda, Rwanda and even further to the Great Lakes.

As a result, a ”virtuous circle” could kickstart productivity, economies of scale, cost reduction,

etc. Business wise, these key performance indicators could propel revenue growth and profit

margin to the next level and trickle down to the men and women left behind, in dire needs, by

raising the standard of living and the purchasing power all around the region.

The Horn of Africa Initiative introduced by IGAD in 2019 with an 18 billion US dollars funding

package is a good step in the right direction. It is largely focusing on interconnection-based

projects, with the financial support of the World Bank, the African Development Bank and the

European Union.

So what’s next if it goes haywire? The choice is simple : either the HOA is consumed by

short-sighted and futile gains, engulfed in a “doom-and-gloom attitude” holding it back, jealousy

and suspicion spilling over, in all directions, and ruining the chance to offer a beacon of hope to

their citizens. The aftermath would be cataclysmic, equal to a zero-sum game with no end in

sight.

Or, they will beat the odds, overcome their petty differences, restore trust amid temptations to actselfishly and finally embark on an all-inclusive win-win project steered by Ethiopia and its assets,on steroids, (plentiful electricity supplied by the Grand Renaissance Dam providing up to

5000-6000 MW upon completion, cheap labor, vast arable lands, untapped mineral resources,

nascent industrial base exemplified by Hawassa Industrial Park, huge market and last but not

least, new BRICS status gateway).

When you add it all up, the HOA’s outlook seems, at first glance, blurry and while digging a little

deeper, bleak. Antonio Gramsci who was a towering figure in the realm of Marxism philosophy

once said: “The old world is dying and the new world struggles to be born; in the interregnum a

great variety of morbid symptoms appear”.

In spite of its bountiful assets, lots of pundits prophesize the HOA’s fate doesn’t look good.

Who will step up among its leaders and have what it takes (strategic acumen and bold

leadership) to strengthen bilateral relations, incentivize their nations for the common good,

maximize their comparative advantages in partnership, engage a ”reset” and curb these ”morbid

symptoms”, indifference, distrust, cynicism, just to name a few? The time is ripe before we

witness what these leaders are made of.

more recommended stories

President Irro’s Diplomatic Reset: A Bold Step Toward Somaliland’s Recognition

President Irro’s Diplomatic Reset: A Bold Step Toward Somaliland’s RecognitionBy Abdi Jama Hargeisa — The.

Somaliland Pursues Peace: First POW Exchange with Puntland Completed

Somaliland Pursues Peace: First POW Exchange with Puntland CompletedPresident Irro’s Dialogue-Based Approach Gains Momentum.

From 1960 to Today: Somaliland’s Unbroken Case for Statehood

From 1960 to Today: Somaliland’s Unbroken Case for StatehoodSomaliland’s Foreign Minister Reaffirms Sovereignty, Urges.

Gogol or Goodbye? Somalia’s Last Opportunity for Federal Reconciliation

Gogol or Goodbye? Somalia’s Last Opportunity for Federal ReconciliationBy Abdirahsid Elmi & Mohamed Musa.