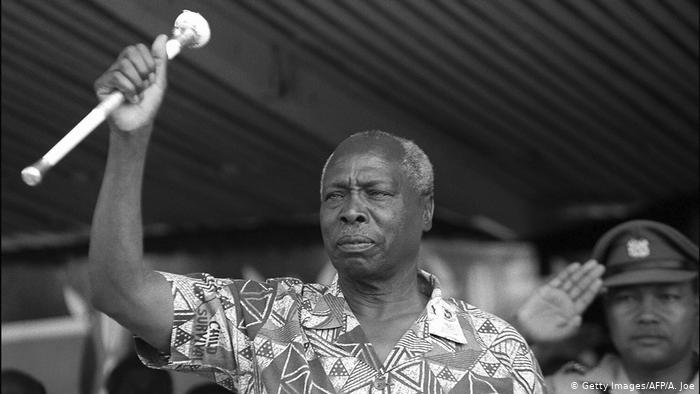

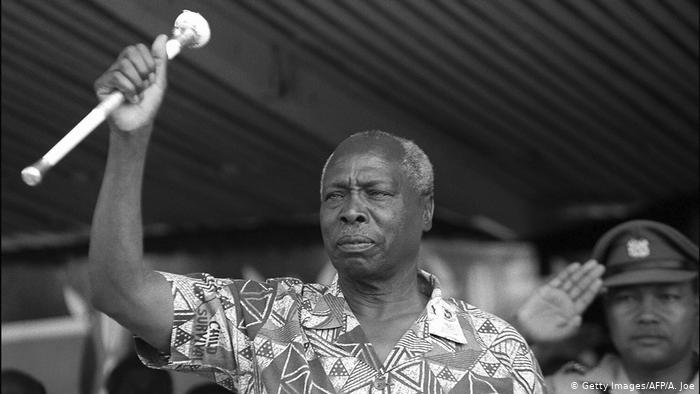

Kenya’s former President Daniel Arap Moi has died at the age of 95.

Mr. Moi was Kenya’s longest-serving president. He was in office for 24 years, until intense pressure forced him to step down in 2002.

I will not go down in history as the man who said nothing over the death of a man who killed, maimed, tortured and sent into exile, dozens of my family members.

Over the three decades he ruled the country any insecurity incident was met with an aggressive response that usually ended badly.

Massacres occurred and abuses were meted out to civilian population on a daily basis. Houses belonging to members of my immediate family were once torched by security forces in an operation locals dubbed “Garissa Gubay”.

In 1984, hundreds of Somalis were murdered in the Wagalla Massacre, Moi’s response to the growing unrest among the Somali, who were frustrated at being alienated from state power.

Repression of the opposition, including the Somali minority, became institutionalized during the 1980s under Kenya’s second president, Daniel Arap Moi. It was Moi who built the now-infamous Nyayo House torture chambers, where he detained real and imaginary opponents without trial.

Many victims later testified to the cruel beatings and psychological torment inflicted upon them there.

Over the years, several massacres have been committed by Moi’s government in the North Eastern Province and thrown under the carpet as established by the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC), a commission mandated after the 2007/08 Kenyan post-election violence to investigate historical injustices and offer recommendations.

Such merciless massacres that were committed by President Moi against its own people in the Northern Eastern Province include the Bulla Karatasi Massacre in 1980, the Wagalla Massacre in 1984 and the Malka Mari Massacre.

The TJRC established that these massacres were aimed at, like the Shifta War responses, mass punishment of entire communities and that yet nobody has been prosecuted for perpetrating them.

The people of the NFD have also experienced a very precarious form of Kenyan citizenship and national identity. While most have resigned to the fate of being Kenyan citizens, the Kenyan government has not treated them in that regard.

Kenya retained the NFD but that did not put an end to the state of dissatisfaction and marginalization amongst people in the area after the shifta war, and the effects of that war and its outcomes are still felt to date.

I still believe that given the opinion of the people living in the NFD at Kenya’s independence, earlier historical factors and the costs of keeping the NFD in Kenya, it would have been more justified for the Kenyan and British governments to allow the NFD to join Somalia, even without fighting the Shifta War.

Both of my parents were born within the territorial boundaries of the British protectorate (What later became Kenya), but when my turn to get an identity card came, it took me a lifetime to obtain the one piece of document that without it would have otherwise meant I could be deported to Somalia.

Getting a passport was an uphill task, changing it to conform with a government directive will be donkeywork’s too, because of my identity.

I sometimes wonder why did Kenya hold my region so dear, refused to give in, fought so hard to ensure it is part of its colonial boundary and later treat the inhabitants of the five Nothern Frontier districts with immense shock and horror.

As I write down this article, I’m away from home, over two thousand kilometers from where I was born. One thing, however, gets clearer as I transverse through towns across horn of African countries, Somalis are one and the same. A Somali, wherever he is in the world is not defined by the papers he holds but by his origin.

more recommended stories

Somaliland’s Berbera Industrial Park: A New Era of Investment and Job Creation

Somaliland’s Berbera Industrial Park: A New Era of Investment and Job CreationThe Government of Somaliland, under the.

President Irro’s Landmark Visit to UAE: A Diplomatic and Economic Win for Somaliland. Dubai, UAE – Somaliland’s Diplomatic Breakthrough

President Irro’s Landmark Visit to UAE: A Diplomatic and Economic Win for Somaliland. Dubai, UAE – Somaliland’s Diplomatic BreakthroughBy: Abdi Jama President Dr. Abdirahman.

Kenya’s Unjustifiable Interference in Sudan: A Grave Violation of International Law and Regional Stability

Kenya’s Unjustifiable Interference in Sudan: A Grave Violation of International Law and Regional StabilityBy: Abdi Jama Kenya’s continued meddling.

𝗙𝗼𝗿𝗺𝗲𝗿 𝗣𝗿𝗲𝘀𝗶𝗱𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗠𝘂𝘀𝗲 𝗕𝗶𝗵𝗶’𝘀 𝗥𝗲𝗰𝗸𝗹𝗲𝘀𝘀 𝗔𝗰𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻𝘀 𝗠𝘂𝘀𝘁 𝗡𝗼𝘁 𝗕𝗲 𝗜𝗴𝗻𝗼𝗿𝗲𝗱 – Abdihalim Musa

𝗙𝗼𝗿𝗺𝗲𝗿 𝗣𝗿𝗲𝘀𝗶𝗱𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗠𝘂𝘀𝗲 𝗕𝗶𝗵𝗶’𝘀 𝗥𝗲𝗰𝗸𝗹𝗲𝘀𝘀 𝗔𝗰𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻𝘀 𝗠𝘂𝘀𝘁 𝗡𝗼𝘁 𝗕𝗲 𝗜𝗴𝗻𝗼𝗿𝗲𝗱 – Abdihalim MusaYesterday, Somaliland witnessed a deeply troubling.