ormer Zimbabwean leader Robert Mugabe, in power for 37 years, died at 95 on Sept. 6. But his legacy, and his ruthless brand of authoritarian politics, lives on through his successor, Emmerson Mnangagwa.

His country, in turn, is suffering. Despite a few nods to economic reform, including a tightening of government spending, Zimbabwe’s economy is collapsing yet again, with fuel, bread, and electricity shortages. In June, the government brought back the much-maligned Zimbabwean dollar, after a decade of using the U.S. dollar and other currencies, instantly cutting savings accounts tenfold. Inflation that month reached 175 percent before the government abruptly stopped publishing official statistics.

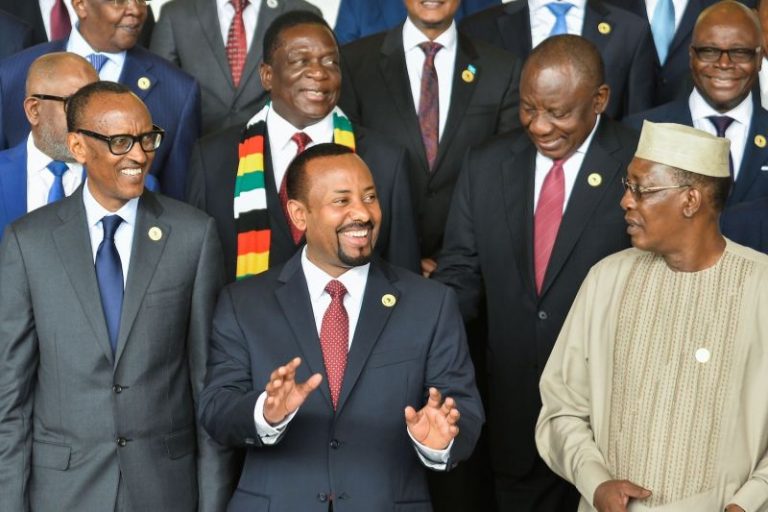

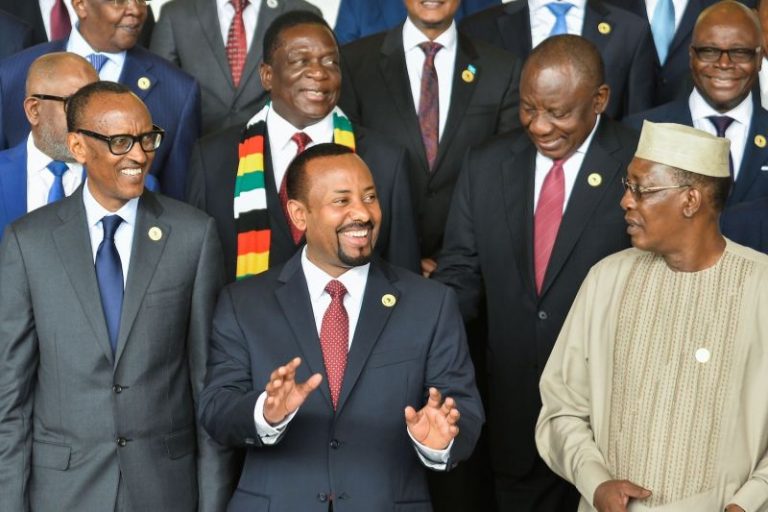

In another African country struggling with the legacy of dictatorship, however, the future looks more hopeful. Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who came into office in 2018, has pushed to liberalize his country’s economy as well as its political landscape. He has overseen the adoption of new regulations regarding civil society, moved toward a diplomatic thaw with Eritrea, and appointed a former opposition party candidate to the country’s electoral board.

The nascent gains in Ethiopia offer a stark contrast to Mnangagwa’s leadership record in Zimbabwe, even though both came to power promising sweeping reforms and a break with their predecessors’ dictatorial ways. And although Abiy and Mnangagwa inherited semi-authoritarian political systems, with long-standing ruling parties and powerful militaries, they have very different relationships to the old guards and have taken starkly different approaches toward their economies. Abiy’s ascent involved breaking with the previous agenda of his party, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), using legitimate institutions. In contrast, Mnangagwa’s seizure of power was enabled by a coup that further bound him to the military, hurting the chances of genuine reform.

Now, at a time when outside powers are calibrating how they respond to political transitions around the world, particularly in Sudan and Algeria, the divergent paths of Ethiopia and Zimbabwe illustrate their precariousness and offer lessons for how the international community can support democratization processes in Africa and beyond.

Ethiopia’s political transition began in February 2018, when Abiy took over from former Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn, who resigned following years of unrest and a deteriorating economic situation. Abiy, despite his security service experience, is a more earnest reformer not necessarily beholden to the old guard in the EPRDF. Though Abiy’s party, the Oromo Democratic Party, is one of the four main constituent parties of the EPRDF, it has not traditionally been the strongest one. While his tenure is a continuation of EPRDF rule, as a reformer from a “junior partner” within the coalition, the tenor of his governance demonstrates breaks with the EPRDF hard-liners’ agenda in a number of ways.

In June 2018, Abiy ended the state of emergency that his predecessor had placed the country under. He appointed an opposition leader, Birtukan Mideksa, who had previously been imprisoned for her work, as the head of the country’s electoral board, signaling commitment to a free and fair election in 2020. He oversaw the loosening of Ethiopia’s tight restrictions on foreign funding of civil society organizations that work on human rights issues, and the Ethiopian Parliament removed three major rebel groups from the country’s official list of terrorist organizations.

Soon after the state of emergency was lifted, Abiy reshuffled critical posts in the country’s security sector, replacing the army chief of staff and the director of the National Intelligence and Security Agency. The move was widely interpreted as weakening the position of the dominant faction within the EPRDF, the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). It also hinted at the scale of his ambition to usher in a new era of Ethiopian governance and reshape the balance of power within the EPRDF.

Shoring up the country’s faltering economy, whose past years of double-digit growth were bolstered by government investment enabled by taking on foreign loans, is another area where Abiy has made some initial progress. While Mnangagwa sits atop a collapsing economy that benefits only a few, Abiy has pushed to liberalize Ethiopia’s. He aims to fully privatize state-owned sugar plants, industrial parks, and railways, as well as partially privatize the four crown jewels of Ethiopia’s economy, including Ethiopian Airlines. Such reforms have profound political implications, dislodging long-established economic interests and marking a reversal from the EPRDF’s previous agenda of state-led growth (which has been linked to inefficiencies and corruption).

Ethiopia’s process of liberalization has not been linear—nor has it been universally popular or entirely peaceful. The arrests of several high-profile military and political figures early in the administration raised tensions between the TPLF and Abiy’s supporters, with the former claiming ethnic discrimination. In June 2018, a grenade was tossed into the crowd at a rally for the prime minister, injuring more than 100 people and killing two. One year later, in June 2019, the army chief of staff was killed by his bodyguard, and the Amhara regional governor was slain by the regional head of security. Abiy’s response to these assassinations, which included mass detentions and an internet shutdown, echoed the tactics of previous EPRDF administrations.

Source: FP,

more recommended stories

President Irro’s Landmark Visit to UAE: A Diplomatic and Economic Win for Somaliland. Dubai, UAE – Somaliland’s Diplomatic Breakthrough

President Irro’s Landmark Visit to UAE: A Diplomatic and Economic Win for Somaliland. Dubai, UAE – Somaliland’s Diplomatic BreakthroughBy: Abdi Jama President Dr. Abdirahman.

Kenya’s Unjustifiable Interference in Sudan: A Grave Violation of International Law and Regional Stability

Kenya’s Unjustifiable Interference in Sudan: A Grave Violation of International Law and Regional StabilityBy: Abdi Jama Kenya’s continued meddling.

𝗙𝗼𝗿𝗺𝗲𝗿 𝗣𝗿𝗲𝘀𝗶𝗱𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗠𝘂𝘀𝗲 𝗕𝗶𝗵𝗶’𝘀 𝗥𝗲𝗰𝗸𝗹𝗲𝘀𝘀 𝗔𝗰𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻𝘀 𝗠𝘂𝘀𝘁 𝗡𝗼𝘁 𝗕𝗲 𝗜𝗴𝗻𝗼𝗿𝗲𝗱 – Abdihalim Musa

𝗙𝗼𝗿𝗺𝗲𝗿 𝗣𝗿𝗲𝘀𝗶𝗱𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗠𝘂𝘀𝗲 𝗕𝗶𝗵𝗶’𝘀 𝗥𝗲𝗰𝗸𝗹𝗲𝘀𝘀 𝗔𝗰𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻𝘀 𝗠𝘂𝘀𝘁 𝗡𝗼𝘁 𝗕𝗲 𝗜𝗴𝗻𝗼𝗿𝗲𝗱 – Abdihalim MusaYesterday, Somaliland witnessed a deeply troubling.

ADFD pledges to support Somaliland, after President Irro visit

ADFD pledges to support Somaliland, after President Irro visitThe President of Somaliland, His Excellency.